I never considered the race of my former partner during our earliest moments together. I just saw who I was beginning to love, which was probably why I was taken by such surprise when I experienced a racist remark or two from his family. His family, one of Irish and Italian descent, was seemingly a very tolerant one—they never made me feel “other-ed.” This all changed during a family dinner I’ll never forget.

His grandmother, who I was very fond of and called “Grandma,” invited me every Monday to share a home-cooked meal with her and her grandkids. My boyfriend’s 26-year-old brother, who I will refer to as “Frank,” was quite the jokester. Often both problematic and offensive, you had to just deal with Frank’s jokes or you’d be considered “soft.” I actually found him funny most of the time. Back then, I would tell myself that his roughening humor served as a blanket for his true sensitive interior. Now I know that isn’t an excuse.

He made fun of those he was comfortable with to make his loved ones laugh. It was apparent, though, that he’d never shared an intimate space with a black outsider, as some of his pranks were racially tone-deaf by nature. Like the time I wore a head wrap to a Monday night dinner when breakfast was served for supper and Grandma made pancakes. Frank called me over to show me who my “aunt” was. Confused and curious, I walked over and found him giggling and pointing at an Aunt Jemima’s syrup bottle.

My experience isn’t unique. Alberto Roca, a 22-year-old Latino male, experienced similar tone-deaf commentary from his white girlfriend’s family. “My girlfriend’s mom once told me I dressed well for a Hispanic,” he told me.

In situations like these, it’s important for the partner to intervene and address the matter. If the partner expresses laxity during these moments, it invites similar situations to happen again and again.

Indeed, it happened again.

I attended another one of Grandma’s Monday night dinners with my hair styled in its natural state. Frank blew into my hair to see if it would move. Later that night, he threw small pieces of food at my afro because he knew the food would get stuck. It took me a long time to realize that these were not in fact acts of love or even the slightest bit funny. Not only did they make me hyper aware of the polarity of our two families, but they also brought my attention to my partner’s lack of awareness and passivity in these moments of unveiled microagressions and stereotyping.

The aforementioned struggles of interracial unions are experienced daily. Collective denunciation with interracial relationships dates back centuries. Romantically engaging with a different race in the United States has been taboo longer than it has been tolerated. There once were anti-miscegenation laws that barred blacks and whites from marrying or engaging in sex as early as the 1600s. Fast forward to the 1960s, during the Civil Rights movement, and 24 states across the U.S. still had laws in place prohibiting interracial marriage.

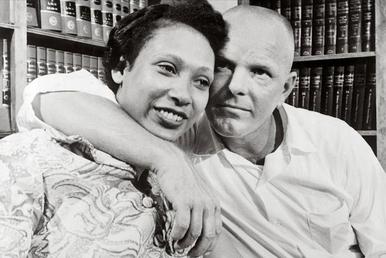

You may have heard of the famous story of Richard and Mildred Loving and the couple’s fight for love in the late 1950s. The newlyweds were taken from their Virginia home and thrown into jail for the crime of getting married. After a prolonged legal battle, the Supreme Court finally ruled that laws prohibiting interracial marriage were unconstitutional in June 1967. Decades later, in Alabama, the last law prohibiting interracial marriage was finally repealed. This was in the year 2000. Basically, yesterday.

Anti-miscegenation laws are no longer in place, but some people still experience punishment from their community for dating outside of their race. The consequences often include removing a family member from financial or emotional support. Less extreme ramifications include verbal judgment or bullying from friends and family.

Samantha Harvey, a 20-year-old black woman, experienced judgment from her friends for engaging in casual sex with white men and women. “When I had sex with a white boy, my friends were at first surprised and made small jokes and little ‘I knew it’ comments,” she told me. “When I told them I had sex with a white woman, their responses were a little more shocking. One friend said I had experienced ‘colonizer pussy’ and that definitely made me feel a way.”

The colonizer/master versus slave dynamic is an old trope that posits black women as subordinate to their white male partners. This was well-illustrated in an episode of the award-winning NBC series This is Us, when Kevin and Zoe stop at a gas station. Kevin approaches the cashier, who does not acknowledge the two as a couple, despite them clearly being together. The clerk also only makes eye contact with Kevin while snubbing Zoe.

Brianna Bicking, a 23-year-old biracial woman, remembers having a similar experience: “There was a time when I was 10 and my parents and I went to [my dad’s] predominantly white church for Easter. It was time to give peace and no one wanted to shake my mother’s hand since she was black. That’s when I realized things are different for us.”

Annette Voll, a 23-year-old Latina, knows the feeling well. She, being a white Hispanic, and her partner, being a black man, have summoned frequent reactions from outsiders. “The comments towards Rachide and I were all about him getting this beautiful light-skinned girl and questions about what he did for a living to be on vacation at this beautiful resort, with me,” she said. “I can’t help but recognize the internalized self-hate that is also carried with those ‘compliments.’”

Harvey expands on this deep-rooted issue, but with the roles reversed. “The only issue with ‘respect’ from white men, is that it feels conditional,” she said. “It feels like their respect is [afforded] only because they find me exotic, a fetish, or something they’ve always wanted to try. There is a sense that, as a cis-white male, you feel entitled to everything, including my black body.”

Some white partners and their families are aware of these racist behaviors; they may even attempt to atone for the mistakes of their ancestors. Sometimes, though, they go about doing so the wrong way.

Taylor Watson, a 22-year-old black woman, recounts an uncomfortable moment with her British partner’s mom. “When I first met his mother, she gave me a book about slavery as a gift,” Watson told me. “It was a super awkward moment and he recognized that it was inappropriate and vehemently apologized for it. I think it was her way of trying to relate to her son’s girlfriend. She saw it as an ‘I saw this and thought of you’ gift…but I was a little insulted.”

Not every interracial couple experiences more negative clap back than positive. Zoe Stryker, a 21-year-old Polish Jew, has been dating her Dominican boyfriend since high school. She describes her experience in her relationship as a mostly educating and enriching one. “When I go to a holiday dinner at his house, I feel proud to be in my own skin because his family supports me. We talk about the differences in our religions and cultures, making each other appreciate our union that much more.”

It’s possible to foster healthy interracial relationships, but it requires patience and open mindedness when navigating public spaces and deconstructing prejudices. It also requires recognizing that both partners experience different worlds and cultivate perspectives based off the color of their skin.

Some find intrigue and beauty in this challenge. Others cling tightly to their own community and wish to preserve their identity.

Nicole DeMarco, a 30-year-old white woman, aligns strongly with the former. “Love is beautiful no matter what color or ethnicity it may be,” she said. “You might encounter close-minded people in life that will never understand the reasoning behind interracial dating and relationships, but that should never stop you [from loving].”